Post Graduate Program in User Experience Design

McCombs School of Business x Great Learning, University of Texas at Austin

Austin, TX (Online), In-Progress (expected completion in Fall 2025)

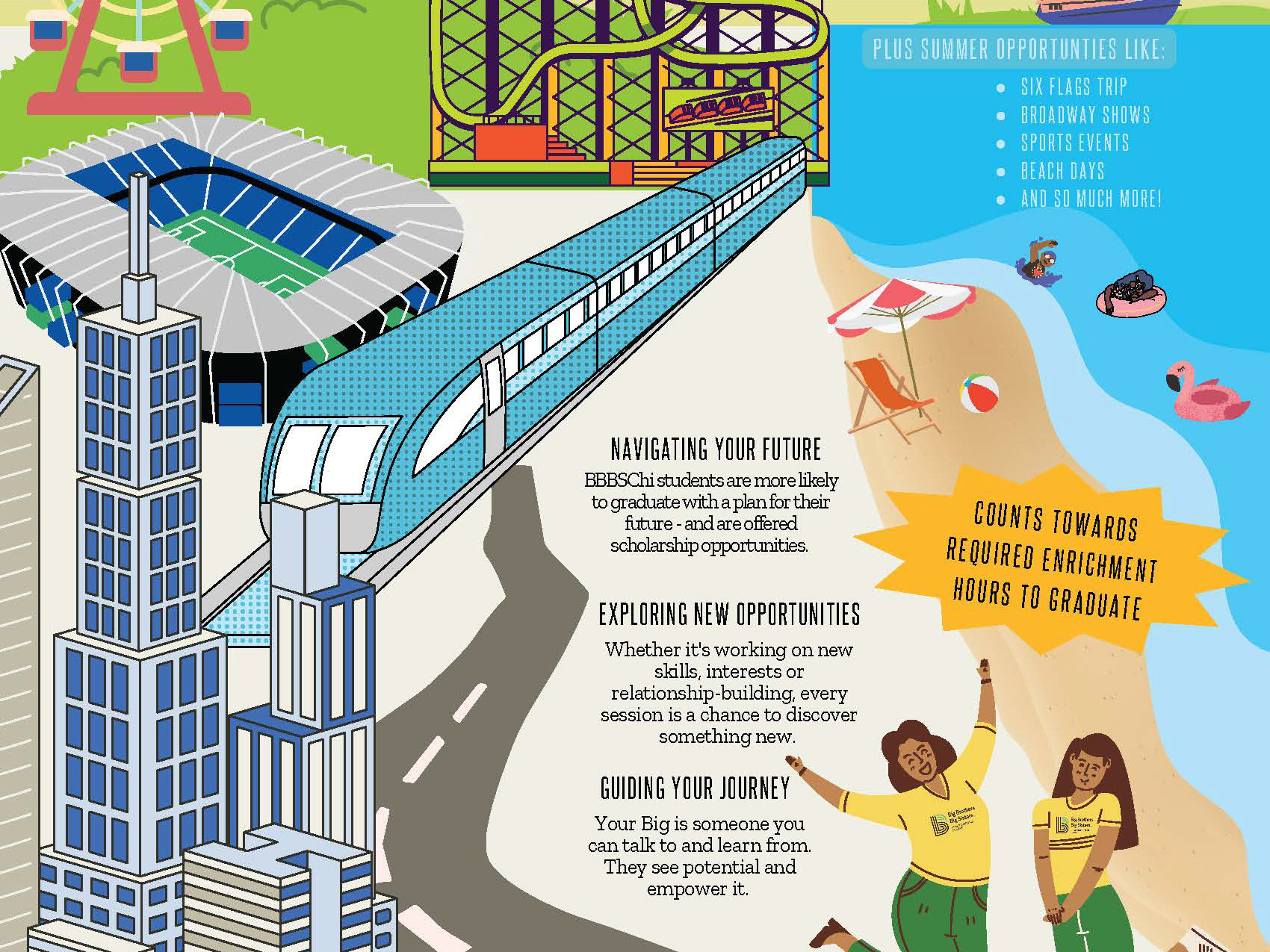

Experience: During my time as a Partnership and Program Facilitator at Big Brothers Big Sisters, I learned that every decision—whether in communication, program flow, or design—directly impacts how people engage and feel supported. Seeing how small details could influence participation and outcomes made me realize the importance of thinking through the entire user experience.

This inspired me to pursue a postgraduate degree in User Experience Design, where I could blend my background in graphic and instructional design with a stronger focus on user research, interaction design, and accessibility. My goal was to create solutions that aren’t just visually appealing, but thoughtfully designed with the user’s needs, emotions, and journey in mind—whether they’re learning, viewing, or making decisions that impact their lives.

Design Leadership Reflective Essay (Sep. 2025)

At Big Brothers Big Sisters of Chicago, there was one event every year that everyone both loved and dreaded: the Six Flags trip. On paper, it sounded like a dream assignment—take hundreds of kids and their mentors to an amusement park for a day of fun. In reality, it was a logistical challenge with buses, budgets, and family expectations to juggle, and the event had such a reputation that staff often joked about steering clear of the planning team altogether. And that’s exactly when I found myself leading it.

I didn’t step in because I thought it would be easy — I knew why no one else wanted the role, but I also knew how much it meant to the families we served. For many kids, this was the highlight of their year, and I wasn’t about to let it fall apart. Taking the lead tested my patience and creativity, but it also showed me what kind of leader I could be and taught lessons I now carry into how I think about design leadership.

The “curse” of the Six Flags trip was well known in the office, with past years marked by late buses, poor communication, and frustrated families. At the first planning meeting, the silence when the question of leadership came up was almost comical, as everyone shifted in their chairs, avoiding eye contact and waiting for someone else to volunteer. I finally raised my hand, not because I wanted recognition, but because the event deserved someone willing to take ownership.

That decision put me at the center of everything: coordinating with Six Flags Great America staff, negotiating with donors, fielding questions from families, and keeping staff engaged when enthusiasm waned. It was the first time I had to step fully into a role where people relied on me to set direction and keep things moving, and while it was intimidating, it gave me the chance to shape the event in a way that went beyond logistics. At its core, the event was about creating an experience that reminded our Bigs and Littles why their relationships mattered, and I wanted to make sure that purpose guided every choice we made.

The first challenge was the budget. Tickets, buses, and food were covered entirely by donor funding, and the amount was fixed. As I ramped up communication and marketing to ensure families knew about the opportunity, interest grew far beyond what the budget allowed. High demand was a good sign, but it created an immediate problem: more matches wanted to attend than we could afford, and I had to figure out how to address the gap without letting people down.

The second challenge came from the planning team itself. While several staff volunteered at first, enthusiasm faded as the weeks went on, and tasks began slipping through the cracks. In some cases, I was able to coach and reassign responsibilities, but in one case, I had to escalate the issue to our CEO. It wasn’t enjoyable, but it reminded me that accountability is part of leadership, especially when the whole group depends on everyone doing their part. Families added another layer of difficulty, and because I was the primary point of contact, I had to deliver tough news about ticket limits—mentors and mentees only, no siblings or extended family—which required balancing empathy with clarity.

Finally, there was the weight of history. The event’s reputation for stress had some staff convinced we were destined for another disaster before we even began. Beyond handling logistics and communication, I had to push back against that mindset and convince people that this year could be different if we stayed organized and disciplined. Overcoming that sense of inevitability became just as important as solving the logistical problems themselves.

To tackle these challenges, I focused on structure, communication, and reframing problems as opportunities. Early on, I brought the planning team together for a brainstorming session that worked like a mini “scrum”: we mapped out tasks, flagged potential trouble spots, and matched responsibilities to people’s strengths and interests. Giving people ownership in this way made them more invested in the work, and it gave me a clearer picture of who I could rely on as the event drew closer.

I also built in weekly check-ins with agency leadership—my manager, the director, and CFO. These meetings kept the event visible, aligned us on budget decisions, and gave me a sounding board so I wasn’t carrying every decision alone. The budget issue required the most creativity, and rather than turning families away, I pitched donors on the idea that Six Flags wasn’t just a trip but a key part of the mentoring experience. By framing it as an investment in relationships that created lasting memories, donors responded with an additional $6,000, which allowed us to purchase 150 more tickets.

Managing the planning team meant balancing empathy with accountability. When staff members struggled, I offered support and reframed tasks to make them manageable, but when that didn’t work, I escalated issues. It wasn’t pleasant, but it was necessary, and I learned that addressing problems directly is far better than letting them fester. I also looked for practical ways to improve the experience for families. Setting up a GroupMe channel made day-of communication smoother, especially during departure, and the post-event survey gave us both testimonials and concrete advice for future improvements. These extra steps weren’t required, but they elevated the event in ways that mattered.

When the day arrived, the difference from previous years was clear. We had over 500 attendees across eight buses with 35 staff, and the detailed planning paid off. Check-in was smooth, transportation ran with only a short delay, and departure was efficient—no hours-long hold-ups like before. The result was an event that felt calm, organized, and joyful rather than stressful and chaotic.

Families and mentors shared how meaningful the day was, and one child told us it was “the best day of my life,” which made all the stress worth it. Staff, who had dreaded the event in the past, admitted they were surprised at how smoothly it went. At the next quarterly meeting, I received the High Achieving Award, with the entire staff voting unanimously. While it was humbling to be recognized, the award felt more like a symbol that the event had transformed from one of the agency’s most dreaded responsibilities into something we could take pride in.

Looking back, I was struck by how much I enjoyed leading, even when it meant dealing with the difficult parts. I had stepped in because no one else wanted to, but once I was in it, I realized I thrived on the combination of coordination, problem-solving, and motivating others. I learned that when the stakes are high, I tend to lean in rather than back away, and that instinct helped me through the hardest parts of planning. If I could do it again, I would start earlier and schedule regular check-ins with staff handling day-to-day tasks. That structure would prevent last-minute scrambles and show that leadership is about support as much as oversight.

These lessons connect directly to design leadership, where the goal is not just the end product but the environment that makes strong outcomes possible. Leading Six Flags showed me that good design leadership means creating the conditions for collaboration, finding creative ways around constraints, and advocating for the value of what you’re building. Collaboration was evident in how I distributed tasks and worked with donors; innovation appeared in practical solutions like using GroupMe and reframing donor pitches; and advocacy was central to positioning the event not as a field trip, but as an investment in mentorship. More importantly, the experience shaped how I see myself as a leader: someone who balances empathy with accountability, communicates across diverse stakeholders, and reframes challenges into opportunities. I aim to bring empathy and collaboration to every project because I’ve seen how those traits foster trust and motivation, while also connecting strategy to vision so that the work is not just completed but completed with purpose.

That insight shapes how I think about design leadership: not just as a product or a deliverable, but as a process built on collaboration, creativity, and strategy. As I grow into future leadership roles, I want to step into challenges others avoid, bring clarity where things feel uncertain, and always keep the human impact at the center. If a day at an amusement park can become the “best day of my life” for a child, then thoughtful, intentional leadership—whether in program management or design—has the power to shape experiences that last far beyond the moment itself.

Project 2: Information Architecture (IA), Sitemaps, and User Flows (June 2025)

Task: Imagine you've been appointed as a UX designer for a start-up gearing up to launch a travel planning and booking platform. You will compete in a market that has established players such as Tripadvisor, Booking.com, Kayak, etc. However, your company, being a new entrant, is confident that they will be able to create a unique and user-centric experience in the Travel Industry. You will:

- Pick one existing platform within the Travel Industry and create a sitemap of its website

- Create an Information Architecture map for your company's website, illustrating the proposed structure

- Create a user flow of searching and booking a stay on your company's proposed website

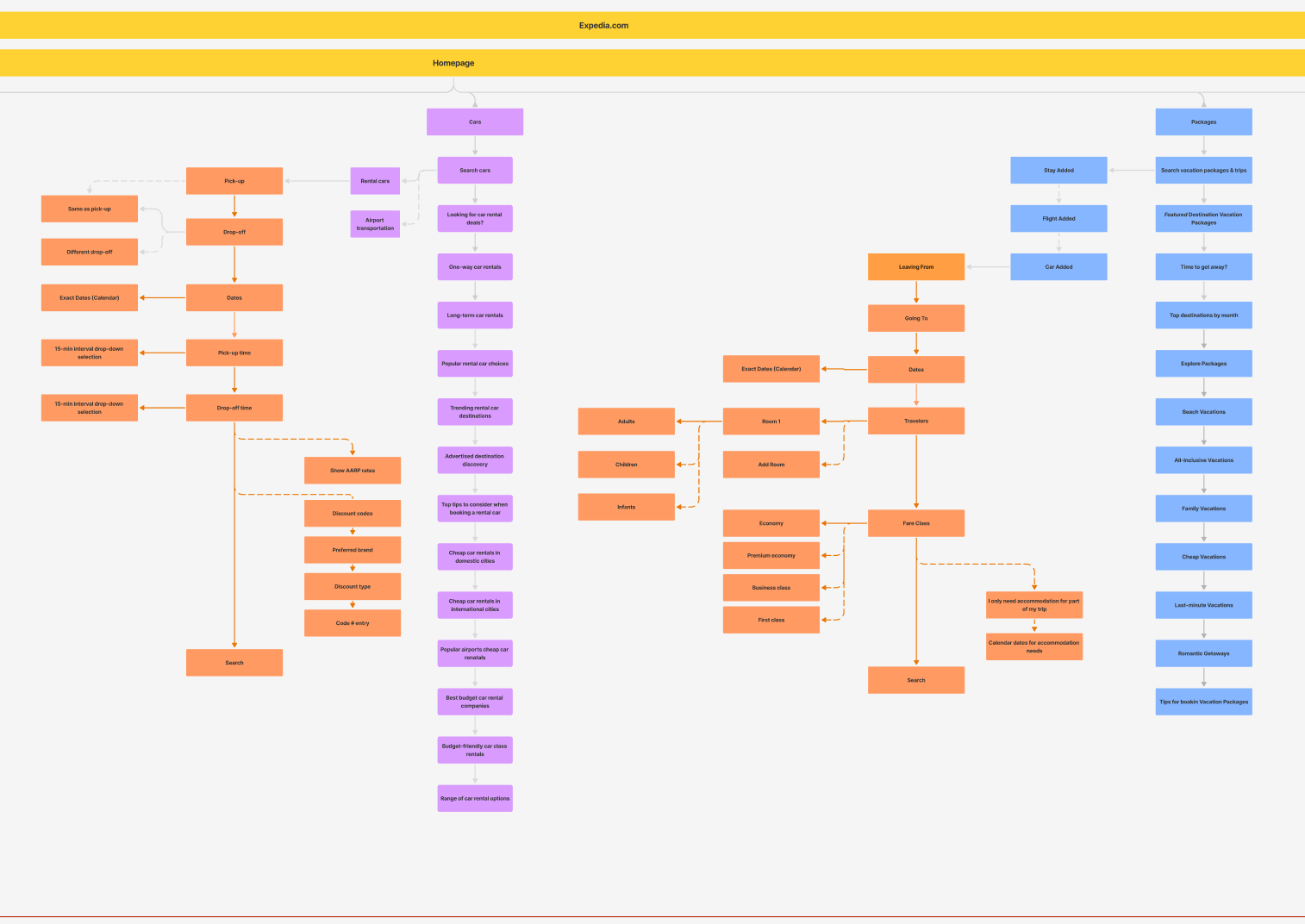

Design Analysis: For this project, I began by analyzing the sitemap and information architecture (IA) of Expedia.com, one of the leading digital travel platforms. Expedia’s hierarchy—from Stays to Cruises—reflects user priorities and brand positioning, with a consistent page structure that emphasizes deals, trending destinations, and travel types. This analysis helped me understand how established platforms organize content and user flows to balance business goals with usability.

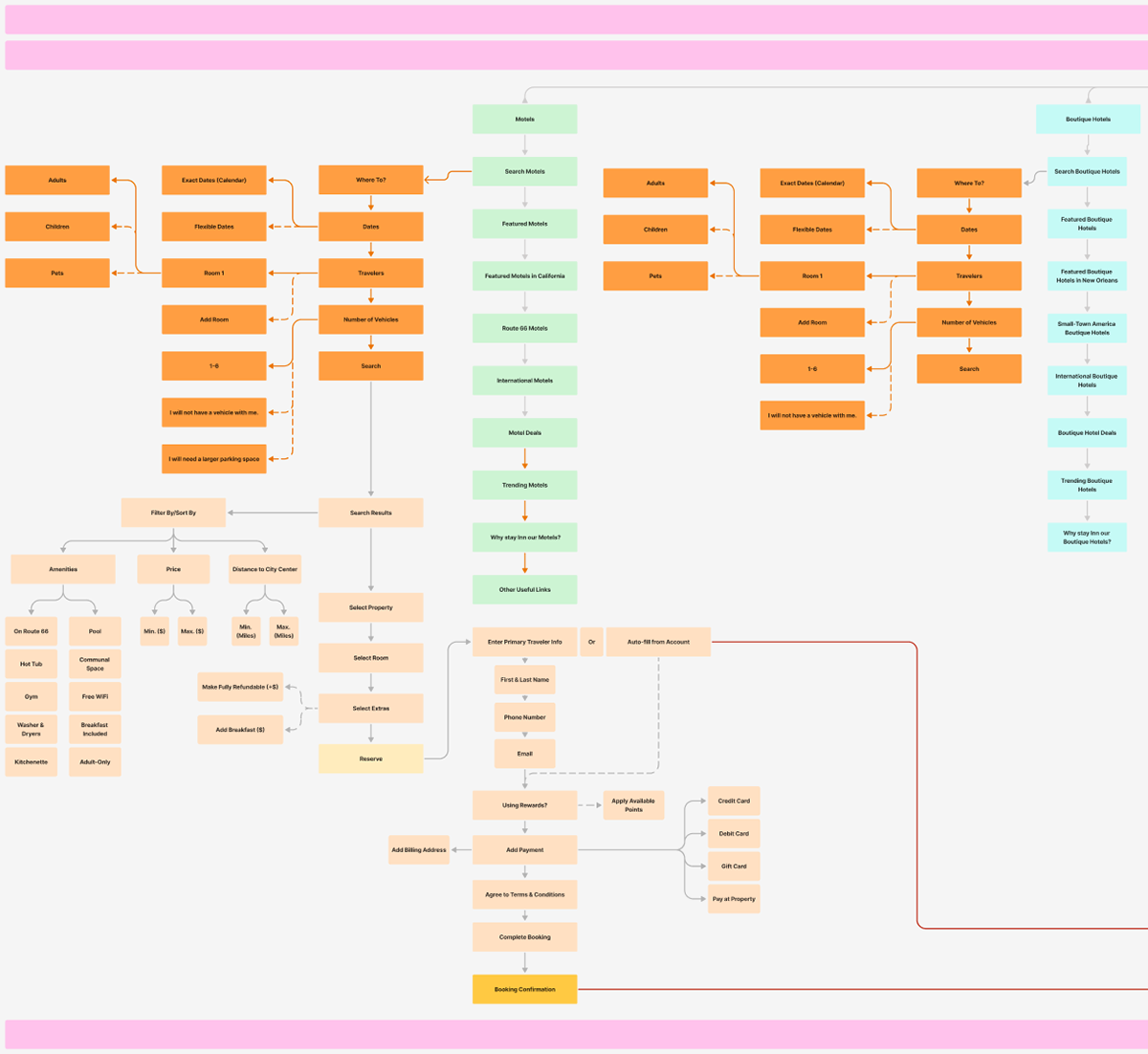

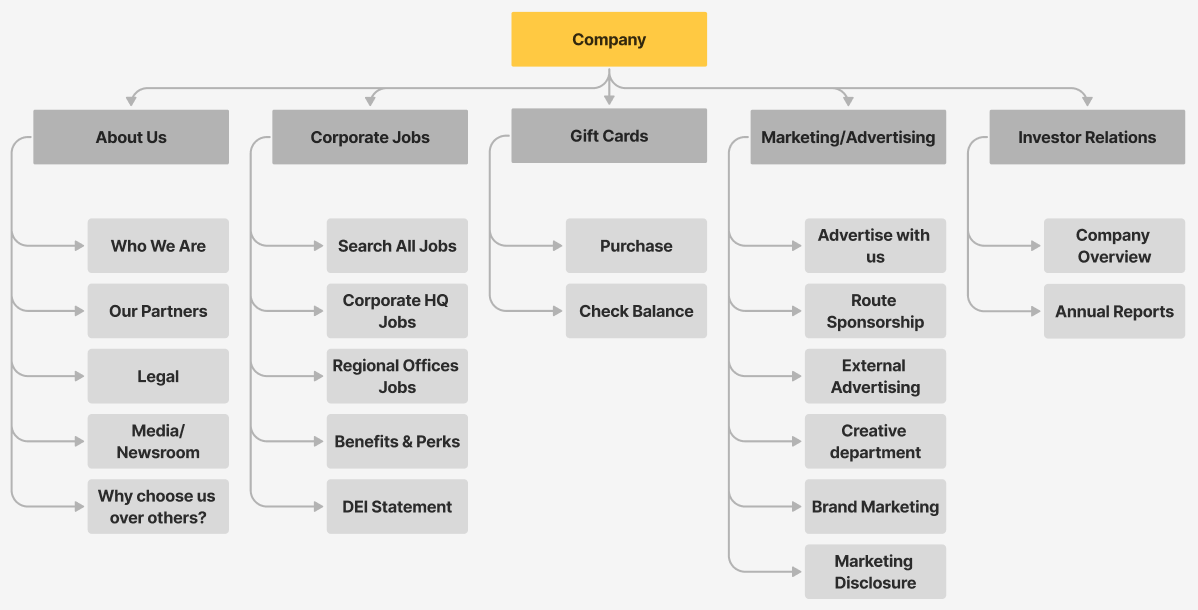

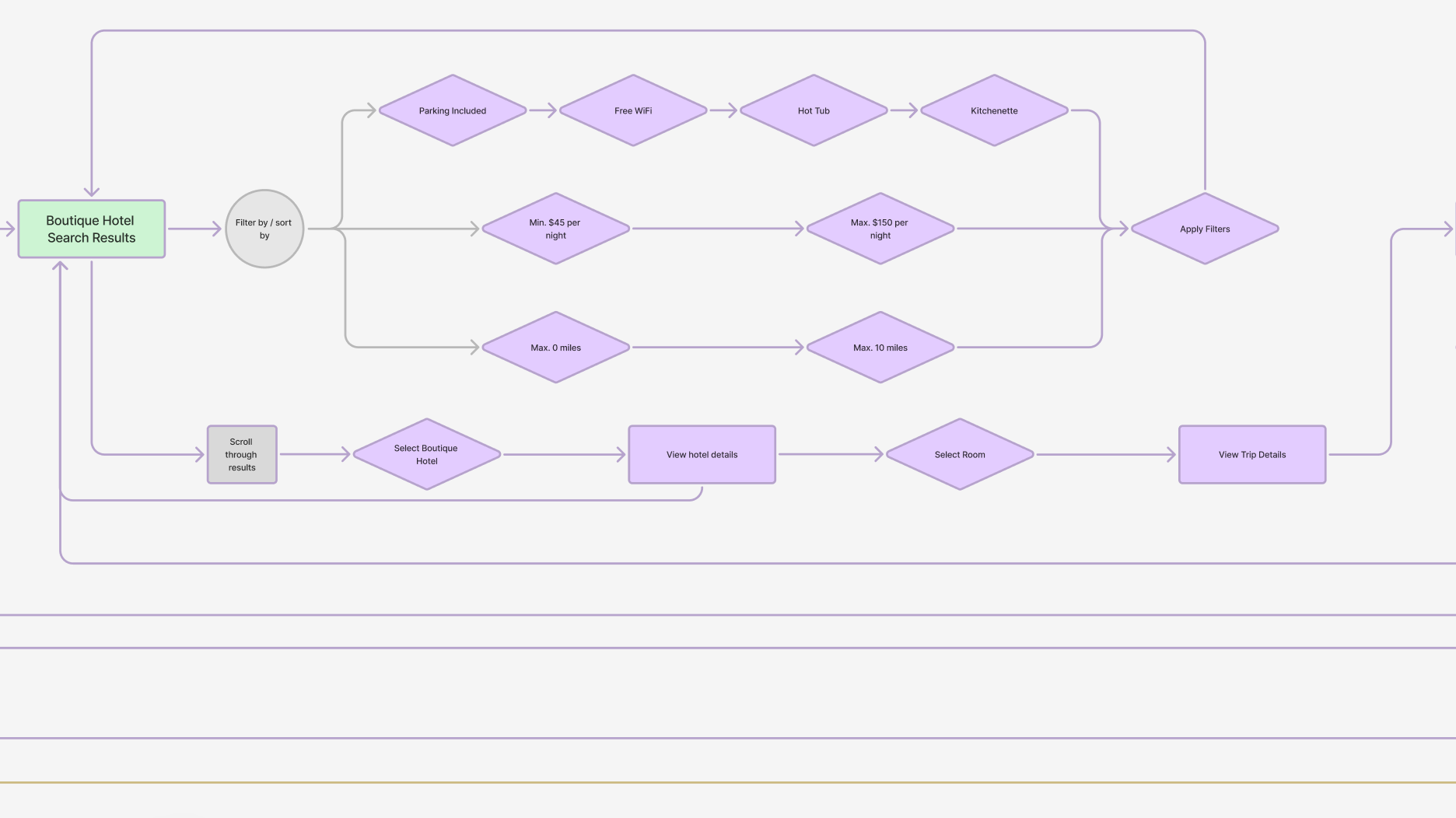

Using these insights, I designed the IA, sitemap, and user flow for Inn Route, a travel platform focused on independent motels, boutique hotels, and campsites. Inspired by hotel rewards programs like Marriott Bonvoy, Inn Route offers standardized booking flows and a unified rewards system while preserving each property’s unique identity. A key IA feature is the “Routes” concept—curated, bookable road trip itineraries that create an experience-driven alternative to chain hotels. I also accounted for the property-owner side of the platform, which would require a separate, backend-focused IA.

Tools Used: FigJam, Google Slides

Use this button to access the Google Slides Report of the overall project:

To access the FigJam boards for the Expedia.com Sitemap Case Study, and the Inn Route IA and User Flow, use the corresponding buttons below:

Samples from the project are shown in the photo grid below:

Project 1: User Research, Competitive Analysis, User Personas, and User Journey Maps (May 2025)

Task: Assume that you're a UX designer for a new app in the Music Streaming Industry. Your company has charted out a plan to create an app similar to the major players in the streaming industry. In a market dominated by established players, your company is a new player eager to make a mark. Your mission is to understand the target audience by conducting user research. The goal is to reveal different user types, their motivations, and the challenges they face when streaming music. You will:

- Conduct Primary Research by creating a survey, float it to 10 real people, and summarize the results & key insights that should be shared with the design team

- Create two user personas representing distinct segments of your target audience.

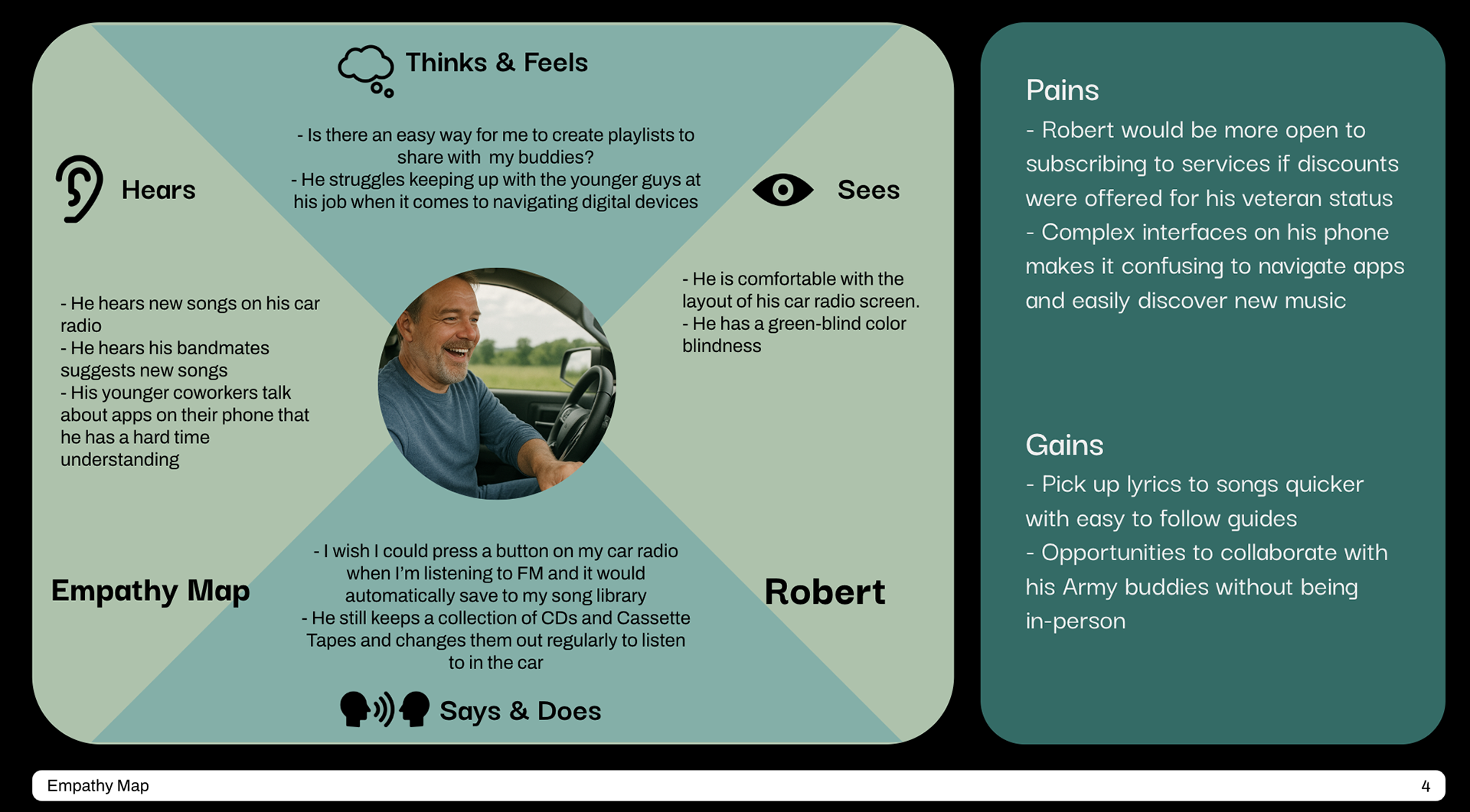

- Develop an empathy map for each persona to gain deeper insights into their thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

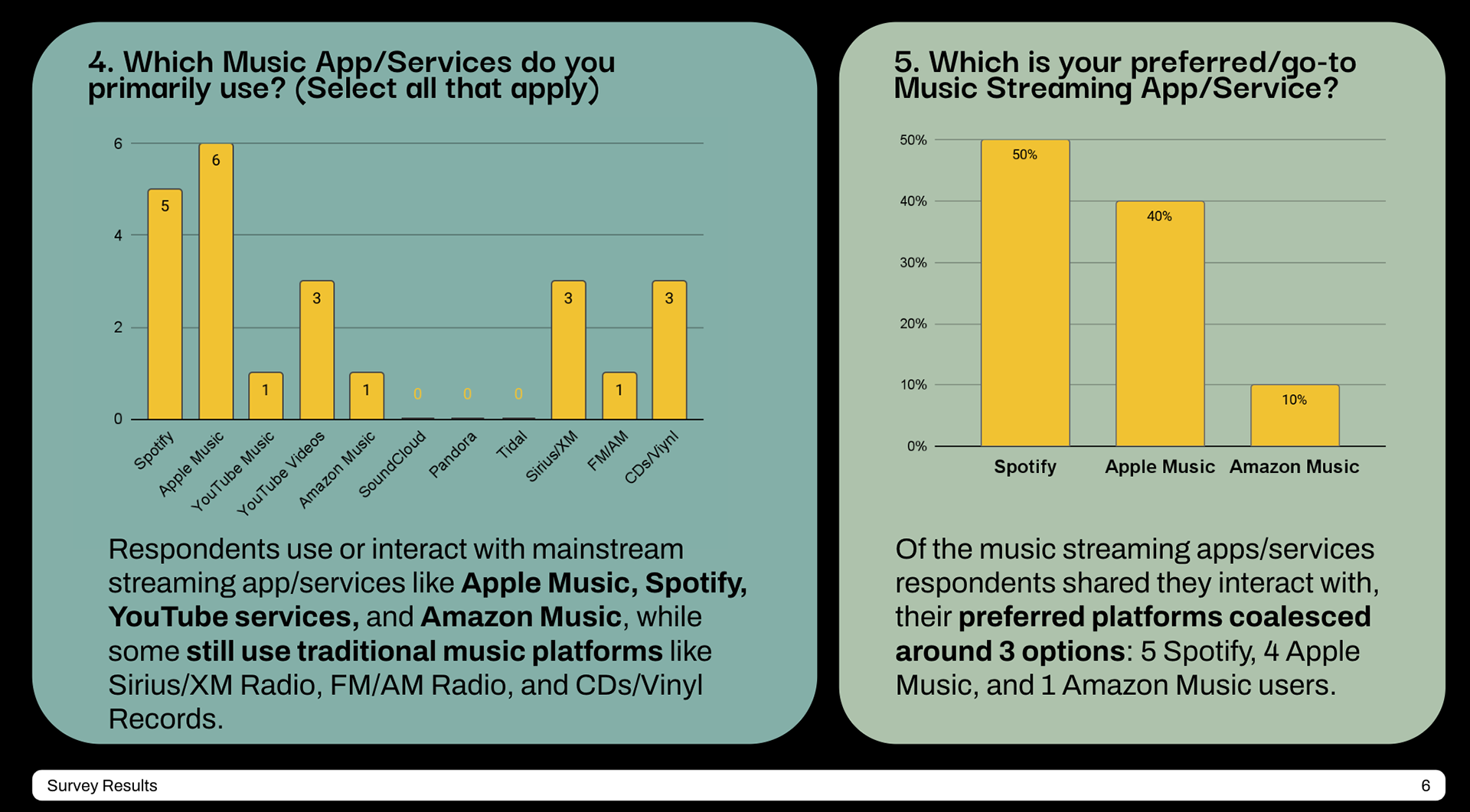

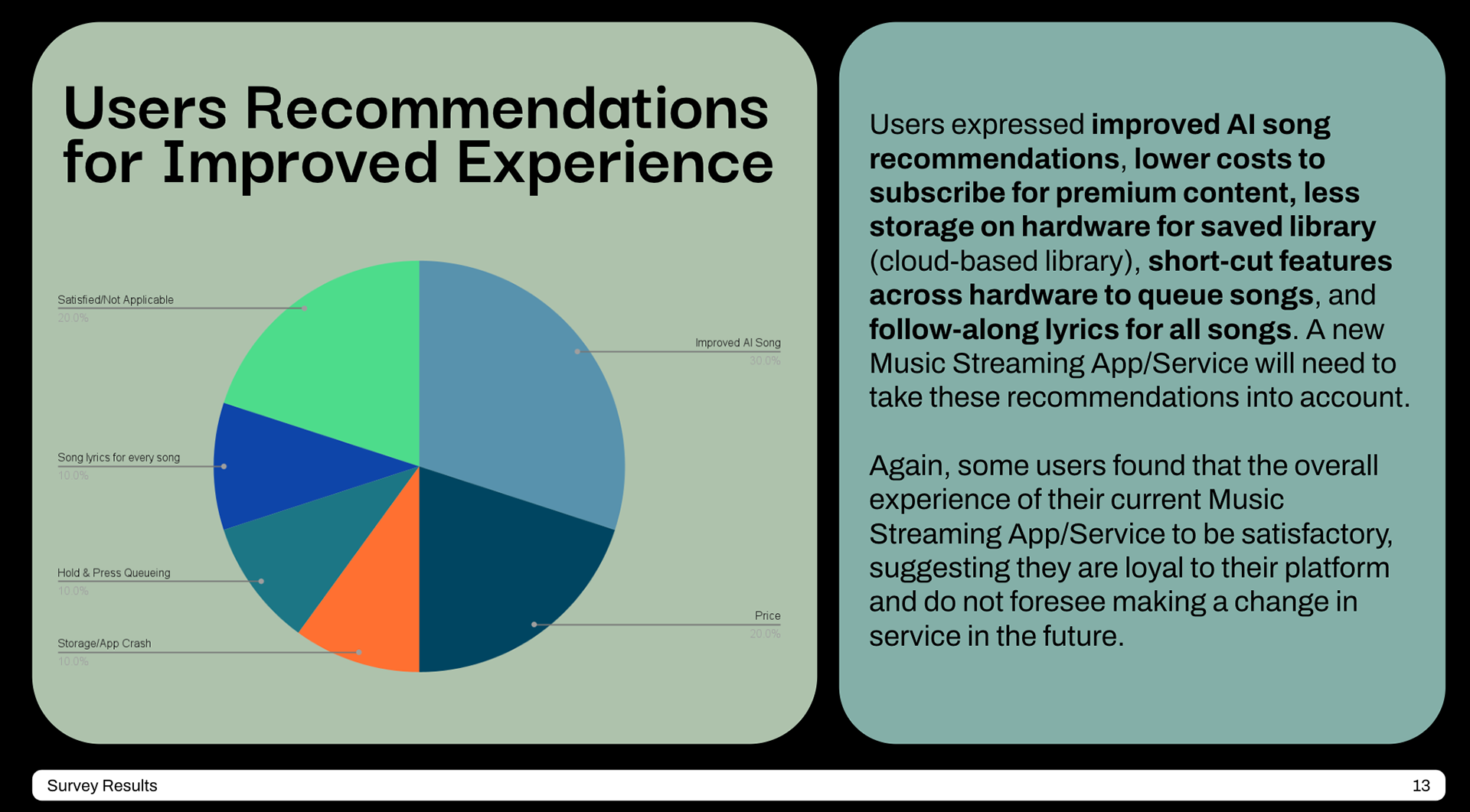

Design Analysis: Through market research, it became clear that breaking into the music streaming space would be difficult due to high user loyalty and limited brand switching. When designing my survey, I focused on identifying both pain points and loyalty drivers within existing services. The results revealed two clear user segments:

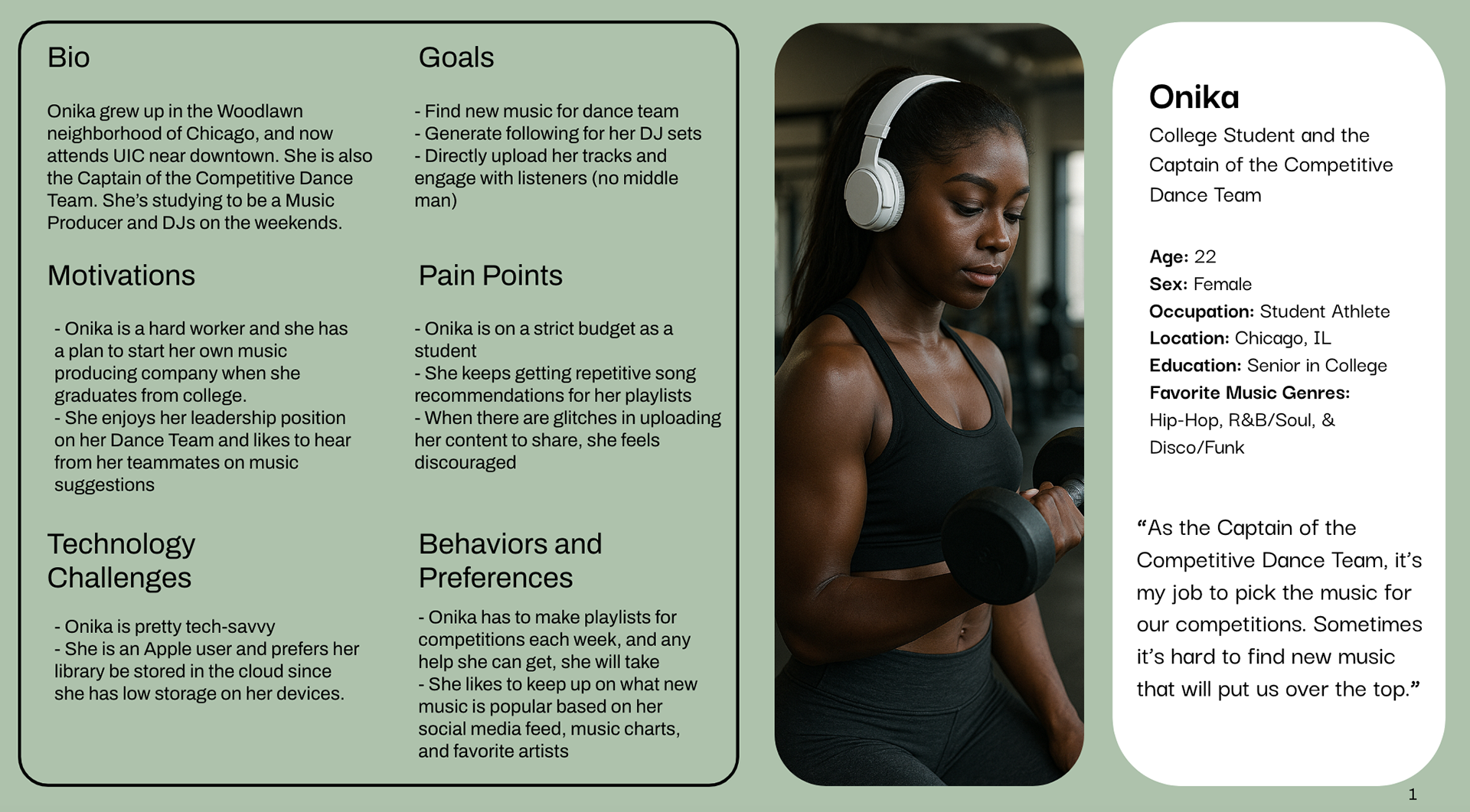

- Onika, a tech-savvy college student and aspiring music producer frustrated by poor recommendation algorithms and limited tools for reaching new listeners.

- Robert, a middle-aged construction manager and retired veteran who, despite being more traditional, is eager to discover new music, but wants an intuitive interface and affordable pricing.

Both personas shared concerns beyond interface design, including pricing structures and user status-based discounts (e.g., student and veteran discounts) that could influence their decision to switch platforms.

Taking these insights into account, I recommended that the new app mimic familiar user interface patterns (like the simplicity of a car radio) while also introducing social networking features for emerging artists, creating a unique niche that blends music discovery with community-driven engagement.

Tools Used: Google Forms, Google Sheets, Google Slides

Use the button to access the Google Survey, Survey Results (Sheets), Survey Analysis (Slides), and User Persona & Empathy Maps (Slides):

Samples from the project are shown in the photo grid below: